By TED LIPIEN

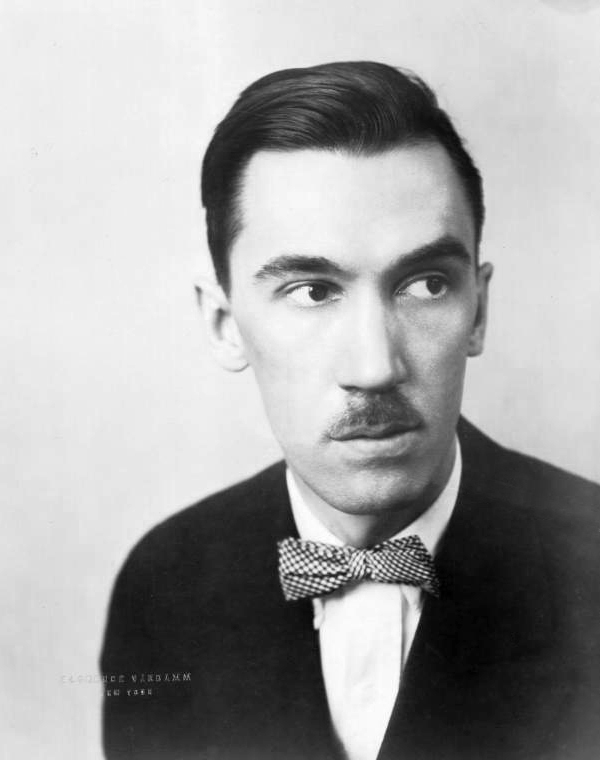

The name of the handsome man with a tanned Latin complexion in the 1942 publicity photo was Edward Raquello. He was a Hollywood actor, but he soon became known as a “very talented terror” at the Voice of America (VOA), the U.S. government radio station broadcasting abroad, where he was hired that year as a producer and put in charge of training radio announcers during World War II and later in the early years of the Cold War. Before his Voice of America career, he played Latin lovers in a number of Hollywood films. Radio Daily, the national newspaper of commercial radio and television, referred to him in a report on July 7, 1943 as being “once known as the ‘Polish Valentino’ at the time the late Carl Laemmle brought that European film star to to Hollywood.” The paper praised his role as the “Polish immigrant” in a radio play titled America the Beautiful. Had we known earlier that Edward Raquello was the voice of the Polish immigrant, the paper wrote “the thrill to our ears wouldn’t have been so unexpected” “[His]splendid performance” Radio Daily added, “will be remembered (at least by this reporter) for many years,”[ref]Radio Daily, “Main Street Old Scoops Daly,” July 7, 1943, page 4. https://www.americanradiohistory.com/Archive-Radio-Daily/RD-1943/RA-1943-07.pdf.[/ref]

His American friends called him Eddie. Raquello was his American name. His name in Poland, where he was born on May 14, 1900 to a middle class Jewish-Polish family in Warsaw, then still within the Russian Empire, was Edward Zylberberg (Silberberg). His father died when he was a child. He was raised by his uncle, Beniamin Rykwert, the head of the Nożyk Synagogue who supervised his religious education. His mother, who died in 1932, ran a successful bakery and patisserie shop in Warsaw.

While still in Poland, Wowek, as he was affectionately called by his family, changed his last name to a more Polish-sounding name, Kucharski. In 1917, he began studies at the technical university in Warsaw, but his higher education was interrupted by the 1919-1920 war with the Soviet Union. Edward must have been a highly capable young man because he was chosen as a personal driver for Polish general Józef Haller despite the fact that some of Haller’s volunteers were strongly anti-Semitic, falsely accusing Polish Jews of siding with the Bolsheviks. With the exception of a few Polish and Polish-Jewish communists who took orders from Moscow, Edward and many other Jewish students saw themselves as Polish patriots and fought alongside ethnic Poles in the 1920 Battle of Warsaw which stopped and reversed the advance of the Soviet Red Army.

After the Polish-Soviet war, Edward started his acting career in Polish films. He also performed in theaters in Warsaw, Gdańsk, Kraków, Berlin, London, and Paris. An excellent, comprehensive and well-sourced article in Polish by young journalist Marek Teler, titled “Edward Raquello – zawrotna kariera polsko-żydowskiego Latynosa” (“Edward Raquello — A Meteoric Career of A Polish-Jewish Latino”), describes how Edward found his way to Hollywood. Rosabelle Laemmle, the daughter of the Universal Studios founder Carl Laemmle reportedly hired Edward as her dancing partner in Paris when he fell on hard times. She immediately noticed his resemblance to Rudolf Valentino. The party-loving young woman was believed to have persuaded her father to offer Edward a contract with Universal Pictures. He arrived in New York on March 26, 1926.

A Latin Lover and Broadway Actor

Edward’s first Hollywood name was Edward Regino before he changed it to Raquello, possibly to honor his beloved sister Rachel who remained in Poland. Rachel survived the Holocaust, but his other sister, Jentel, was murdered in a German concentration camp together with her husband and their two children.

Edward Raquello’s first notable American role was that of a dancer Raoul in the silent movie The Girl from Rio. Afterwards, his movie career had stalled for a few years, during which he appeared in several Broadway plays, often playing handsome and aristocratic foreigners, mostly of Latin origins. In 1937 he signed a contract with 20th Century Fox and resumed his movie career, appearing in several films, including Charlie Chen at Monte Carlo and Idiot’s Delight with Clark Gable and Norma Shearer in the main roles. In 1938 he became an American citizen. Some of his other film roles were in Missing Daughters (1939), The Girl from Mexico (1939), and Calling Philo Vance (1940). He never became a major Hollywood movie star but had a reasonably successful American career as a film and theatre actor. Marek Teler reported that Raquello promoted Polish culture in the United States and assisted visiting Polish journalists in arranging interviews with film celebrities in Hollywood. In 1940 he played the role of a Polish officer Major Rutkowski in a Broadway production of Robert E. Sherwood‘s play There Shall Be No Night about the 1939-1940 Soviet attack on Finland. The play was directed by Alfred Lunt who admired Raquello’s acting talent and once fired another actor who publicly insulted Edward on stage during a rehearsal. Edward Goldberger, a veteran VOA broadcaster who had worked with Raquello said later in an interview that Raquello had to have provoked the actor to such an unprofessional outburst as he was later known to provoke many VOA broadcasters with his own erratic behavior. One explanation for it might have been that he suffered from an undiagnosed Addison’s disease, but according to Goldberger, Raquello was a unique, talented but difficult person.

But the thing that came into my mind was, he must have been like that then, too. What provoked this guy to do something so unprofessional? It must have been that Raquello was Raquello.[ref]The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series,”EUGENE KERN AND EDWARD GOLDBERGER.” Interviewed by: Claude ‘Cliff’ Groce. Initial interview date: December 12, 1986. Copyright 2000 ADST. https://www.adst.org/OH%20TOCs/Kern,%20Eugene.toc.pdf[/ref]

Hired by Pro-Stalin Voice of America

Edward’s appearances in Robert E. Sherwood’s plays (he also acted in Sherwood’s Idiot’s Delight at the Hanna Theatre in Cleveland, Ohio with Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne) may have helped him to secure a job in 1942 as an announcer and later a program director and regional producer-supervisor (1942-1945) of early Voice of America radio broadcasts in the Office of War Information (OWI) in New York City. According to one of the early VOA broadcasters, Eugene Kern, it was Sherwood who brought Raquello to OWI to work on producing shortwave radio programs to Europe. Raquello found himself among many pro-Soviet foreign and American communists and naive idealists also recruited by the Roosevelt administration to produce anti-Nazi radio, print and film propaganda.

Sherwood, who was also a speech writer for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, was made earlier the director of the OWI’s Overseas Division. Raquello may have also known the first VOA director, theatre producer and Hollywood actor John Houseman who was later accused by the State department of hiring his pro-Soviet fellow-traveler and communist friends in the theatre world to work for the Voice of America.

There is no evidence that Raquello was fooled by Soviet propaganda or wanted to promote it, but in 1942, Houseman and Sherwood also recruited American communist author Howard Fast, the future recipient of the Stalin Peace Prize (1953), to be the chief VOA news writer and news director. It was Howard Fast who determined the content of VOA news and consulted with the Soviet Embassy in Washington. Fast also censored any news critical of communism or Stalinist atrocities.[ref]“I established contact at the Soviet embassy with people who spoke English and were willing to feed me important bits and pieces from their side of the wire. I had long ago, somewhat facetiously, suggested ‘Yankee Doodle’ as our musical signal, and now that silly little jingle was a power cue, a note of hope everywhere on earth…”–Howard Fast, 1953 Stalin Peace Prize winner, best-selling author, journalist, former Communist Party member and reporter for its newspaper The Daily Worker, describing his role as the chief writer of Voice of America radio news translated into multiple languages and rebroadcast for four hours daily to Europe through medium wave transmitters leased from the BBC in 1942-1943. Howard Fast, Being Red (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990), pp. 18-19.[/ref] Raquello may have been required to produce some of Fast’s anti-Nazi propaganda mixed with praise for the Soviet Union and Stalin.

Edward Raquello, who as a Polish patriot fought against the Soviet armies invading Poland, was almost definitely not pro-Soviet nor a supporter of communism. Sherwood, despite his earlier play critical of the Soviet invasion of Finland, later became a major proponent of Soviet propaganda in VOA programs, as did John Houseman who in 1943 was quietly forced to resign by the FDR White House due to the then secret complaints from high-level administration officials in the U.S. State Department and from General Eisenhower who later accused early VOA broadcasters of “insubordination” toward President Roosevelt. FDR himself was more than willing to appease Stalin at the expense of Poland and the rest of East-Central Europe, but not to the point when VOA’s pro-Kremlin propaganda threatened to put American soldiers in danger in North Africa and Italy.[ref]Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965) 279.[/ref]

Some of the broadcasters hired by John Houseman were hardline Communist Party members and were fired, but many of VOA’s European services, remained dominated by Soviet sympathizers while Sherwood continued to coordinate American and Soviet propaganda at the OWI for the remainder of the war.

Among other things, Sherwood wanted to convince VOA’s foreign audiences, including the Poles, that Stalin became a supporter of religious freedom and that any fear of Bolshevism was unjustified.[ref]Robert E. Sherwood, Director, Overseas Branch, Office of War Information; RG208, Director of Oversees Operations, Record Set of Policy Directives for Overseas Programs-1942-1945 (Entry363); Regional Directives, January 1943-October 1943; Box820; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD.[/ref] Sherwood also accepted and promoted the Soviet lie about the Katyn massacre of thousands of Polish POW military officers and government and intellectual leaders, including several hundred Jews.[ref]It is a common misconception that throughout VOA’s history directives from the White House and the State Department were responsible for most of VOA’s propaganda, censorship and news reporting failures. In fact, then as well as today, VOA’s executives and reporters generated much of the propaganda on their own. During World War II, some of VOA’s leaders and programmers were far more pro-USSR and pro-Stalin than the Roosevelt administration wanted them to be. By using the Soviet propaganda line and attacking potential U.S. collaborators in the French Vichy government and the Italian government, VOA was blamed by the Pentagon and the State Department for undermining U.S. war and diplomatic aims in North Africa and Italy. This infuriated, among others, General Dwight Eisenhower and resulted in at least one public rebuke of the Voice of America from President Roosevelt himself. Dozens of communists and Soviet sympathizers, including a few actual Soviet agents, were working at the OWI and the VOA during the war. Their influence over Voice of America’s broadcasts was so powerful that even Left-leaning American labor unions ceased their cooperation with VOA in producing programs about American labor movement issues. Some Communist Party members at the Voice of America were fired during the war, but others remained for a few more years. At least two of them later joined communist regimes in Eastern Europe and engaged in anti-American propaganda.[/ref]They were were murdered by the Soviet NKVD secret police, but the Soviet and OWI/VOA propagandists tried to blame it, falsely in this case, on the Germans.[ref]The Katyn Forest Massacre. Final Report of the Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre pursuant to H. Res. 390 and H. Res. 539, Eighty-Second Congress, a resolution to authorize the investigation of the mass murder of Polish officers in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk, Russia, (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1952), accessed October 26, 2017, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435078695582.[/ref]

Personality Conflict with Broel-Plater

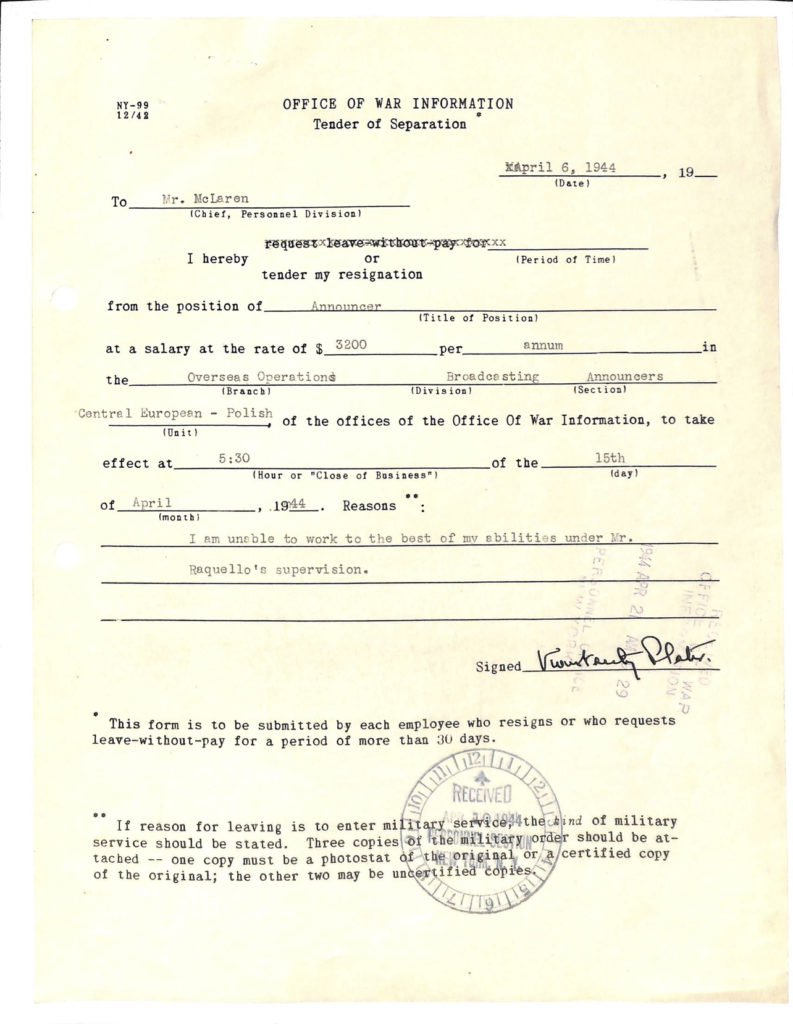

There were some anti-communists among early OWI and VOA journalists, but they were very few and most of them were quickly marginalized. Polish announcer Konstany Broel-Plater, a former Polish diplomat with radio broadcasting and journalistic experience both in Poland and in the United States, resigned in 1944 in protest against VOA airing of Soviet propaganda lies. Jewish-Austrian OWI editor Julius Epstein, who also protested against Soviet propaganda in VOA’s wartime broadcasts, was laid off in 1945.

Edward Raquello’s role during the early years of the Voice of America (the official name for the radio broadcasts was not adopted until sometime after the war) seemed largely limited to producing programs and training radio announcers rather than being responsible for creating program content. The editorial side was left to individuals such as Howard Fast and other pro-Soviet journalists working in accordance of the weekly propaganda directives from Sherwood. Their excessive pro-Stalin zeal eventually became an irritant even to the already strongly Moscow-leaning FDR administration.

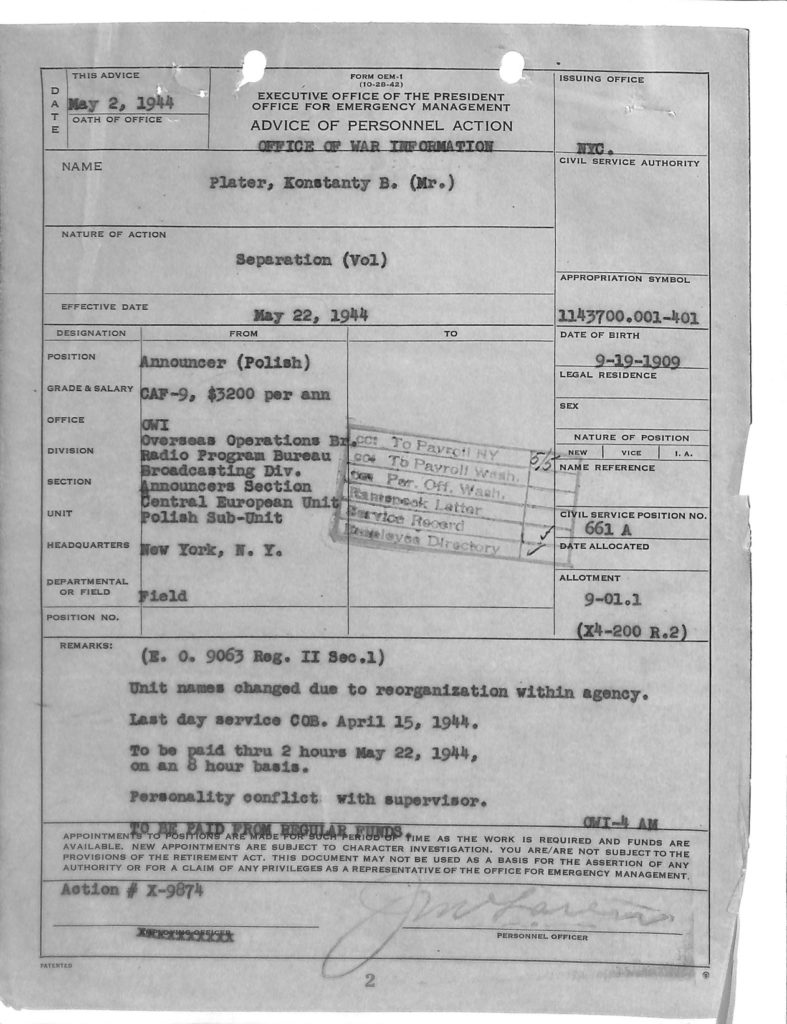

I have found no written record that Edward Raquello either supported or opposed the pro-Moscow line in VOA broadcasts during the war, but, unlike Broel-Plater and Epstein, he did not jeopardize his U.S. government career. In 1945 he was moved from the dissolved OWI to the State Department as a regional producer-supervisor. Raquello was already known by then to be a demanding but sometimes insulting radio producer and supervisor. The personality conflict between him and Broel-Plater is documented briefly in Broel-Plater’s official personnel file, with one note blaming Broel-Plater and another putting the blame squarely on Raquello. The note also mentioned Raquello’s conflicts with other VOA broadcasters. Broel-Plater, a Polish aristocrat with a 1936 law degree from the prestigious Warsaw University and a former diplomat, but also an experienced radio broadcaster who prior to his employment at the Voice of America had written and voiced Polish-American programs for radio stations owned by Columbia Broadcasting System and General Electric, was one of many VOA journalists who had found working with Raquello extremely difficult if not impossible.

In a 2000 interview with a Polish-American magazine, Broel-Plater said that he had refused to read Soviet propaganda and resigned from VOA in 1944.[ref]Teofil Lachowicz, “Zapomniany dyplomata,” Przegląd Polski (New York), October 20, 2000.[/ref] In that interview and with conversations with friends, he did not talk about Edward Raquello in connection with his 1944 resignation. His friends described Broel-Plater, who died in 2007, as a modest and self-effacing man who did not seek publicity. To support his American family after leaving VOA, he had worked for several years as a laborer in a paper mill in Pennsylvania before getting an office job as a lab technician. “When he started working at the paper mill, his co-workers teased him about being a count,” his Polish-American neighbor Elżbieta Palms recalled from her conversations with him. She also remembered him as being a “very humble man” and saying that his aristocratic title didn’t mean much to him.[ref]Elżbieta Palms, e-mail to author, April 26, 2019.[/ref]

Broel-Plater’s decision to leave a well-paying U.S. government job in 1944 appeared to have been politically and journalistically motivated as a protest against propaganda and censorship although his conflict with Raquello may have also played a role. The voluntary resignation form signed by Broel-Plater said: “I am unable to work to the best of my abilities under Mr. Raquello’s supervision.”

At the time when the Soviet Union was America’s most valuable military ally against Nazi Germany, it would have been impossible to make any critical comment in official U.S. government records about Russia or about Stalin, whom VOA and much of private media in the United States were then presenting naively and falsely as a defender of freedom and democracy. But while there is no doubt that Broel-Plater and Raquello disliked one another, this was apparently not a conflict between the two of them based on political differences. Unlike his bosses and many of VOA’s World War II broadcasters, including several who had worked on the Polish desk, it does not appear that Raquello was an admirer of Stalin.

Broel-Plater was not the only VOA broadcaster who found it difficult to work with Raquello because of his explosive temper. Raquello antagonized many VOA journalists who had broader education and more journalistic and radio experience than him, as well as more knowledge of international affairs. While Raquello was well-traveled and knew several languages, he was primarily an actor, and was not a journalist.

As a former diplomat, Broel-Plater knew international politics and also had work experience as a journalist. In March 1943, his supervisor, Casting Director Ruth Ellis, gave him a “Very Good” rating. In submitting a request for a “rapid promotion” for him in August 1943, Ruth Ellis, who was his immediate supervisor, wrote: “Since Mr. Plater has been with OWI (November 1942) he has done consistently good work and has learned our special short wave techniques.” She added that “Mr. Plater’s Polish is excellent and he has been most cooperative.”

Based on his age, education and prior experience, Broel-Plater’s command of Polish was also most likely superior to that of Raquello’s. His immediate supervisor noted Broel-Plater’s previous work as a Polish broadcaster, writer and editor at the Columbia Broadcasting System and his prior work for General Electric as a Polish shortwave announcer “to the complete satisfaction of G.E.” However, his next rating in March 1944 was also signed by Edward Raquello as the Regional Supervisor and reduced to “Good,” with only Broel-Plater’s diction rated as “Outstanding.” This may have been a hint that Raquello had some objections to Broel-Plater’s use of the Polish language or possibly to changes made by Broel-Plater to scripts read live on the air. In his 2000 interview, Broel-Plater alluded to texts written in poor Polish, which he had to correct on the fly, but did not mention the names or identities of the VOA writers and did not mention Raquello. The final personnel form lists “Personality conflict with supervisor,” in this case, Edward Raquello, as the reason for Broel-Plater’s voluntary departure from the Office of War Information.

According to Broel-Plater, prior to his resignation, the OWI office in Washington warned him not to pick a fight with the VOA director over VOA’s pro-Soviet programming. A representative of the Washington office came to New York to talk to Broel-Plater. He invited him to lunch at a restaurant and in a short conversation asked him whether he intends to have a fight with the president of the United States and the Voice of America director. Despite such a veiled threat, Broel-Plater in his own ways tried to struggle with the U.S. government’s radio station’s intensifying pro-Soviet propaganda. As a result, working conditions were made worse for him. He was allowed only to work at night and limited to only announcing the program.[ref]Teofil Lachowicz, “Zapomniany dyplomata,” Przegląd Polski (New York), October 20, 2000.[/ref]

Incidentally and not related to Raquello’s Voice of America career, VOA’s early love affair with Stalin has been covered-up for decades as an embarrassment to the organization which later countered Soviet propaganda during the Cold War. VOA’s silence and promotion of an alternative but largely false narrative of early commitment to truthful reporting have been even more successful than the Soviet coverup of the Katyn massacre.[ref]Voice of America director Amanda Bennett wrote in an op-ed in 2018 about World War II VOA:“Those broadcasts were lifelines to millions. Even more important, however, was the promise made right from the start: ‘The news may be good for us. The news may be bad,’ said announcer William Harlan Hale. ‘But we shall tell you the truth.’” Amanda Bennett, Voice of America Director, “Trump’s ‘worldwide network’ is a great idea. But it already exists.” The Washington Post, November 27, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/trumps-worldwide-network-is-a-great-idea-but-it-already-exists/2018/11/27/79b320bc-f269-11e8-bc79-68604ed88993_story.html.[/ref]

Early anti-communist VOA journalists like Konstany Broel-Plater or Julius Epstein are never mentioned in VOA promotional materials or by former and current VOA officials, and neither is Edward Raquello with the exception of a few archival interviews. John Houseman, who had recruited Howard Fast and other Soviet sympathizers and communists, is still presented as a defender of truthful journalism at the early Voice of America. The fact that FDR’s liberal friends and advisors at the State Department, Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles and Assistant Secretary Adolf A. Berle, forced Houseman’s resignation by refusing to give him a U.S. passport for official travel abroad—their decision supported by the U.S. Military Intelligence—has never been publicly noted by past or current executives in charge of the Voice of America.[ref]Adolf E. Berle, Navigating the Rapids: 1918-1971, ed. Beatrice Bishop Berle (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovic, Inc., 1973), 440. The memorandum about Soviet and communist influence within the wartime Voice of America, signed off with a cover memo by Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, a distinguished career diplomat and a major foreign policy advisor to President Roosevelt and his personal friend, was forwarded to the White House with the date, April 6, 1943. The attached memorandum with the addendum listing names of individuals who had been denied U.S. passports for government travel abroad was dated April 5, 1943. The documents were declassified in the mid-1970s and have been accessible online for some time from the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website and the National Archives. It appears, however, that they have never been widely disclosed and analyzed before now. They were presented for the first time with a historical analysis on the Cold War Radio Museum website. Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles April 6, 1943 memorandum to Marvin H. McIntyre, Secretary to the President with enclosures, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum Website, Box 77, State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944; version date 2013. State – Welles, Sumner, 1943-1944, From Collection: FDR-FDRPSF Departmental Correspondence, Series: Departmental Correspondence, 1933 – 1945 Collection: President’s Secretary’s File (Franklin D. Roosevelt Administration), 1933 – 1945, National Archives Identifier: 16619284. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/16619284.[/ref]

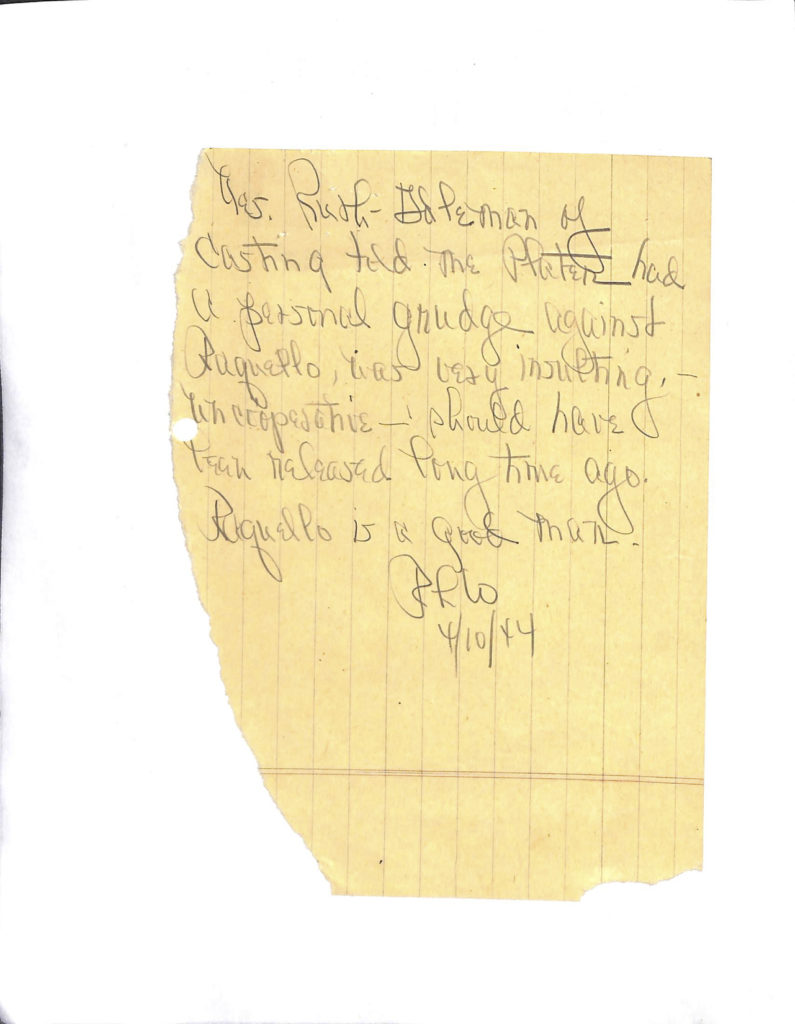

Mrs. Ruth Haleman of Casting told that Plater had a personal grudge against Raquello, was very insulting — should have been released long time ago. Raquello is a good man.

RRW

4/10/44

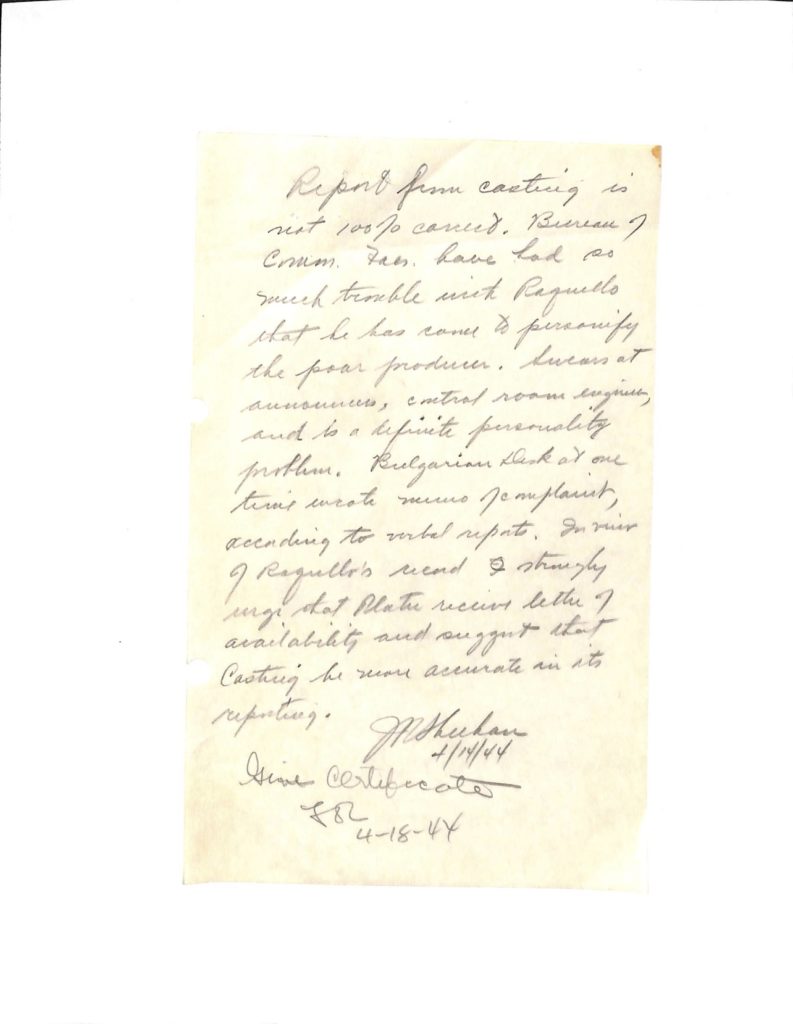

The other note in Broel-Plater’s OWI file questioned the accuracy of the defense of Raquello’s behavior and is supported by several other accounts.

Report from Casting is not 100% correct. Bureau of [illegible words] have had so much trouble with Raquello that he has come to personify the poor producer. Swears at announcers, central room engineers, and is a definite personality problem. Bulgarian Desk at one time wrote memo of complaint, according to verbal reports. In view of Raquello’s record I strongly urge that Plater receive letter of availability and suggest that Casting be more accurate in its reporting.

[M. Sheehan]

4/14/44

Give certificate.

[Illegible initials]

4-18-44

“Talented Terror”

VOA broadcasters who had worked with Raquello invariably described him later as a demanding and valuable producer and trainer but extremely difficult to work with.

In commenting on Raquello’s role as a producer of first VOA Russian broadcasts in 1947 (VOA did not broadcast in Russian earlier in order not to upset Stalin), one of the early VOA broadcasters, Alexander Frenkley, made these observations in an interview recorded for the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training (ADST) oral history project on August 5, 1988.

…and then there was our good friend Eddie Raquello, to whom I think those who started working then and worked for years owe an absolute debt of gratitude. He may have been pedantic and extremely difficult to deal with but he gave us a technical basis, a notion of what broadcasting means, including such amusing points as when he was training his announcers, men and women, he said, “You always have to speak with a smile on your lips, because then the listener will feel that you are a friendly broadcaster. So whatever you have to say, say it with a smile.” But on the other hand he was very strict and demanding, and he thought of things, some of which I still use in the preparation of my scripts today, as a free-lancer. We remained very good and close friends for the rest of his life.[ref]The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series “ALEXANDER FRENKLEY Interviewed by: Cliff Groce.” Initial interview date: August 5, 1988. Copyright 2009 ADST. https://www.adst.org/OH TOCs/Frenkley, Alexander toc.pdf .[/ref]

In an interview conducted for ADST on August 20, 1988, one of the early VOA producers Tibor Borgida made these observations about Eddie Raquello:

So we started working together on the Hungarian, and then they told me to organize the Czechs and the Bulgarians and, unbelievably, also the Albanians, and Romanians. Raquello came in, and they gave him the Polish programs. He wanted the Czechs badly, and in the beginning they gave him the Czechs, and when they did Dr. Adolf Hofmeister [Hoffmeister], who was the chief of the service, and later on became the Czech ambassador to Paris, objected. “Why can’t we have Borgida? His native tongue is Czech, he’s a doctor of law from Czechoslovakia, he was a journalist, he worked for Radio Prague, and you are giving us a Polish guy?” They left Raquello in the job until the Czechs raised hell.

[…]

And that’s the way it was till the end of the war when the Voice was taken over by the State Department. Then I became executive producer for the European Division. They took it away from Raquello for various reasons and put him in the Russian service.[ref]The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series, “TIBOR S. BORGIDA, interviewed by: Cliff Groce.” Initial interview date: August 20, 1987. Copyright 1998 ADST. https://adst.org/OH TOCs/Borgida, Tibor S,toc.pdf [/ref]

Borgida did not explain that the Czechoslovak government Dr. Hofmeister served as Ambassador to France after his wartime employment with the Voice of America was the repressive Soviet-dominated communist regime in Prague. A few other former OWI/VOA journalists also went to work for communist regimes in East-Central Europe. Some like Stefan Arski, also known as Artur Salman, worked for the Soviet-controlled Polish regime in Warsaw as anti-U.S. and anti-Western propagandists. Dr. Hofmeister eventually broke ranks with the pro-Soviet hardline government after the 1968 Prague Spring. VOA’s early love affair with Stalin and communism and initial support for establishing pro-Soviet communist governments in East-Central Europe is almost never mentioned by former OWI officials and journalists, but it does not appear that Edward Raquello had much sympathy for communism. In December 1951 he appeared for the last time as an actor in a televised play I Was Stalin’s Prisoner. It depicted the imprisonment in Hungary for 527 days of American business executive Robert Vogeler whom the communist authorities arrested, tortured and accused of spying.

Without commenting on the political profile of World War II Voice of America broadcasts, two other early VOA programmers, Eugene Ker and Edward Goldberger, described Edward Raquello as “a very talented terror” in his work as a radio producer.

Eddie Raquello was a terror, a very talented terror. One day one of the correspondents he was working with started to strangle him — literally. This was a guy named Max Tak, a Dutch correspondent. At that time Eddie Raquello’s job was to handle a group of foreign correspondents working in New York, to expedite what they wanted to do, much the way the foreign Press Centers operate today.

KERN: They ware paid by their own people, but we also paid them.

GOLDBERGER: He had Dutch, Danish, Belgian, Norwegian, Finnish — he may have had a couple more. Max Tak had been a hero of the resistance in the Netherlands, was a very well known correspondent, and a very easy-going guy. But this particular day, Eddie was making Max go over and over what he was trying to read, and at one point he walked into the studio, leaned over the table to say more, and Max just reached up and seized him by the throat. That’s what Eddie Raquello was like. He was a perfectionist.

KERN: He used to pressure these guys to put in propaganda. And with some it went over easily, they accepted it happily. Others refused. We had to keep it down with Eddie. It’s okay to make suggestions, we told him, but they’re independent people. “Well,” he said, “I’m paying them.” And he was. You see, it was a dual-payment arrangement, which was probably unethical if not illegal, but we had to do what we were told to do.[ref]The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series, “EUGENE KERN AND EDWARD GOLDBERGER. Interviewed by: Claude ‘Cliff’ Groce.” Initial interview date: December 12, 1986. Copyright 2000 ADST.https://www.adst.org/OH TOCs/Goldberger, Edward.toc.pdf.[/ref]

In his book Voice of America: A History, former VOA deputy director of programs, Alan L. Heil, Jr., describes an amusing incident involving Edward Raquello, which was also mentioned by Edward Goldberger. It appears that at some point Eddie, then working at in New York City where the Voice of America had its headquarters from 1942 until 1953 asked the Washington office to record an hour of clear sound at the Lincoln Memorial. Someone in the Washington office simply stuck a microphone out of the window and sent the tape to Eddie. Raquello immediately got on the phone and yelled that there is no street traffic at the Lincoln Memorial. The Washington office had to send an engineer to record one hour of clear sound at the Lincoln Memorial as demanded by Eddie.[ref]Alan L. Heil, Jr., Voice of America: A History (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 40.[/ref]

In recalling Eddie Raquello, post-war VOA broadcaster John Hogan said in an interview with Cliff Groce:

…he used to call five minutes or so before closing time, often on a Friday night. Just having to have something from Washington, some outlandish request. The silent sound tape he wanted from inside the Lincoln Memorial was just the last straw. He always went around with a little bit of wet cigarette hanging down, dripping ashes. He called everybody Sweetie Pie. Some of the time I was able to talk him out of his wilder requests.[ref]The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Information Series, “JOHN HOGAN Interviewed by: ‘Cliff’ Groce. Initial interview date: September 21, 1987. Copyright 1998 ADST. https://www.adst.org/OH TOCs/Hogan, John.toc.pdf.[/ref]

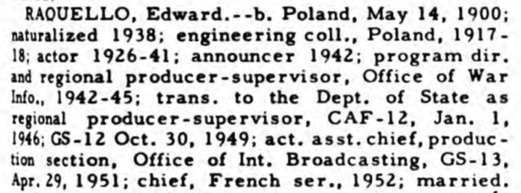

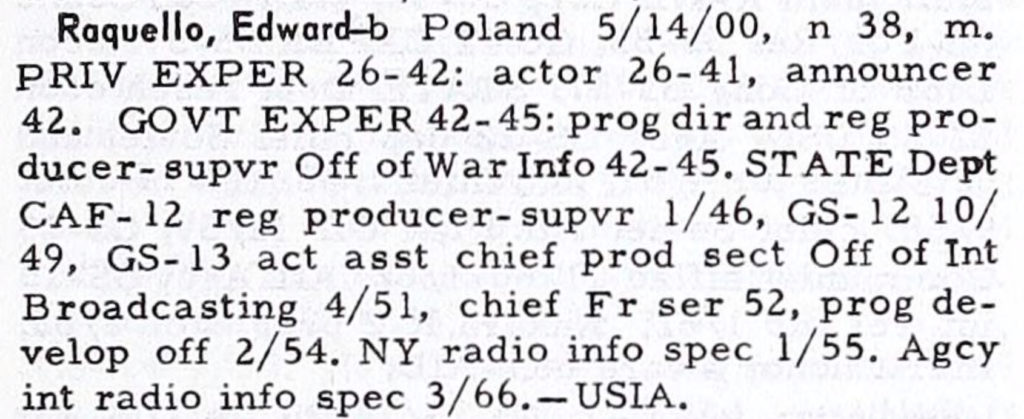

In 1953, the Voice of America was moved from the State Department to the newly-established United States Information Agency (USIA). The 1953 State Department Biographic Register showed the progress in his radio career and lists him as being the chief off the VOA French Service in 1952.

STATE DEPARTMENT BIOGRAPHIC REGISTER 1953, Page 159

RAQUELLO, Edward.–b. Poland, May 14, 1900; naturalized 1938; engineering coll., Poland, 1917-1918; actor 1926–41; announcer 1942; program dir. and regional producer-supervisor, Office War Info., 1942-45; trans. the Dept. State as regional producer-supervisor, CAF-12, Jan.1946; GS-12 Oct. 30, 1949; act. asst. chief, production section, Office of Int. Broadcasting, GS-13, Apr. 29, 1951; chief, French ser., 1952; married.

At some point, Eddie Raquello apparently transferred from his VOA radio production to work on USIA public diplomacy outreach. His State Department/USIA 1967 Biographic Register entry lists his job title in 1966 as Agency International Radio Information Specialist. While the Voice of America headquarters were moved from New York to Washington in 1953, he may have stayed behind at the USIA New York office to assist foreign correspondents based in New York in filing their reports using U.S. government transmitting facilities.

Raquello retired from USIA in 1968, according to his obituary in The New York Times. The New York Times article said that King Baudouin bestowed on him the decoration Chevalier de l’Ordre de Leopold II for his information services in Belgium. He also received the decoration of the Lion of Finland. Edward Raquello died in New York, New York on August 24, 1976. He was survived by his wife, the former Louise Edwards who was a singer and was 28 years younger than Edward. They had no children. He and his wife, who died in 2010, are buried at the Oak Hill Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

In his fascinating article, Marek Teler wrote:

“Edward Raquello had a life full of incredible changes. An aspiring Polish actor with Jewish roots became a Latin lover in Hollywood films and then a demanding boss in the Voice of America.”[ref]Marek Teler, “Edward Raquello – zawrotna kariera polsko-żydowskiego Latynosa,” HISTMAG.org, May 14, 2019, https://histmag.org/Edward-Raquello-zawrotna-kariera-polsko-zydowskiego-Latynosa-18716/1.[/ref]

ALSO READ IN POLISH:

Edward Raquello – zawrotna kariera polsko-żydowskiego Latynosa

Edward Raquello (właściwie: Edward Zylberberg) w krótkometrażowym filmie Man on the Rock z 1938 roku. „Kariera Edwarda Raquello sama przez się przypomina scenariusz ciekawego filmu, pełnego niespodzianek i kończącego się zawrotnym triumfem” – pisało na temat wschodzącej gwiazdy Hollywood „Hasło Łódzkie” 13 stycznia 1929 roku. Pochodzący z Warszawy Edward Zylberberg-Kucharski, który w Stanach Zjednoczonych zmienił nazwisko na Raquello, rzeczywiście stanowi przykład osoby, której życie napisało niezwykle interesujący scenariusz: były student Politechniki Warszawskiej i początkujący aktor, zarabiający na życie jako pan do towarzystwa, nagle trafił do wielkiego świata hollywoodzkich filmów, a w czasie II wojny światowej aktywnie zaangażował się w działalność antywojenną.